Watch this space for upcoming events and reports of recent activities.

Upcoming Events

CIMCIM Conference in London 6-10 September 2020

Hosted Jointly by the Horniman Museum and the Royal College of Music

Conference Title:

Beyond the Object and Back, the Role of Collections in Music Museums

Call for Papers: Deadline Friday 10th February

The same collections often prove capable of telling profoundly different stories. Musical instrument collections have been deployed to support everything from evolutionist narratives to those of decolonization, from systematic organology to those highlighting context, at times prioritising conservation, academic research, display or playability. While some collections reflect individual tastes and interests, others represent collective ideas and the trends, methodologies and cultural priorities of their times. As such, they are powerful mirrors of those times – and indicate the nature of the relationship between music and society itself.

Today, changing attitudes towards audiences and the cultural and social role of museums, the balance between tangible and intangible heritage and the availability of digital technologies are among the many drivers that influence the way museums collect or dispose of objects, choose what to display or preserve, and decide how to deal with the objects that cannot be displayed. Cultural and political agendas, public interest and preconceptions have often played a major role in defining what should and shouldn’t be represented. In some cases, the relevance of collections in museums has even been questioned altogether, while the centrality of objects in displays has been reconsidered, and storage space is an increasing challenge.

This conference aims to present critical perspectives on the ways that music collections represent – or struggle to represent – the ambitions and purposes of the institutions that manage them, throughout history and today. How are music collections responding to changes in the identity of museums? What are the implications for the care and conservation of collections? What is driving, or hindering these changes? In what ways can historical collections still be used to represent current ideas?

Papers are invited in the following formats:

– Full papers 20 min.

– Lightning papers 10 min.

– Panel discussions up to 60 min.

As part of the programme, one session will address the topics above with specific reference to the collecting and playing of historical keyboard instruments and one will specifically address conservation.

A session will be reserved for short communications (7 min), aimed at presenting current projects and updates in the field of music museums, not necessarily related to the theme of the conference.

Please send abstracts of max. 300 words for full papers, or 200 for lightning papers and communications, with clear specification of your full name, institution, address and a brief bio (max 100 words) to the CIMCIM Secretary Marie Martens at Marie.Martens@natmus.dk by 10th February 2020.

Acceptance of papers will be confirmed by the end of February. Accepted abstracts will be published on the conference website soon thereafter. A longer version of the texts and images will be requested by the end of July to be published in the digital proceedings of the conference.

Papers should be presented at the Conference in person by the author (or one of multiple named authors).

Further information and a call for travel grant applications are available at http://cimcim.icom.museum

This event is supported in part by a grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

REPORTS FROM PREVIOUS EVENTS

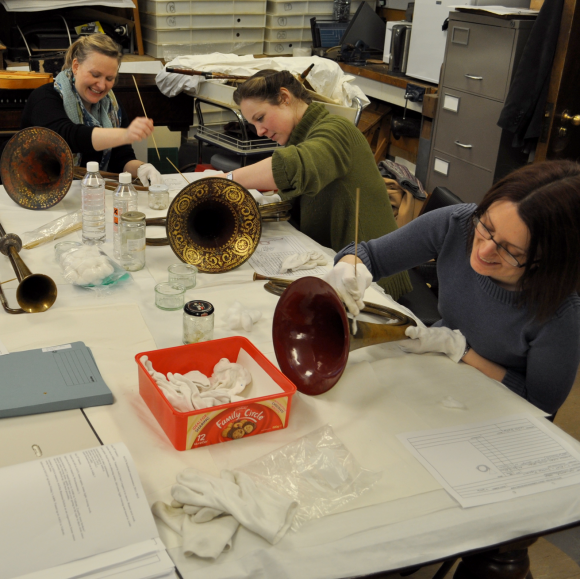

Musical Instruments Unwrapped: Telling Social Histories through Musical Instruments

12 November 2018

Report by Esteban Mariño Garza

Under the morning glow of Santa Cecilia’s elliptical dome, Mimi Waitzman warmly welcomed the members of the Musical Instrument Resource Network (MIRN) and the Social History Curators’ Group (SHCG), and set the tone for keynote speaker Gabriele Rossi Rognoni, who discussed how musical instruments have been used since the most remote times, even earlier than images, to tell our stories. Most museum visitors, according to Rossi Rognoni, experience an unsatisfying separation of the instruments and their function, which places instruments as ‘aestheticized icons and alienates them from their capacity to tell stories.’ Therefore, museums should trigger the emotions of the visitor by being social places: ‘personal, active, provocative and relational.’ Indeed, the stories that an image can tell are less abstract than the possible sound that a historical musical instrument can produce. The sound of an instrument is an image that is recreated by several factors such as the instruments, the performer, the audience and space. A relatively well-preserved image on a wall is already formed for us, while an instrument can produce an endless number of sounds giving us the possibility to create our own sounding pictures. The performance of a musical instrument is the art of connecting the totality of your being with other entities to create music. Professor Rossi Rognoni’s concern is legitimate since the public should have the opportunity of going to a museum and in some way, experiencing the performance of musical instruments. Digitalization and interactive scratches the periphery of what the real experience of playing and hearing a musical instrument, and although, as Rossi Rognoni stated, would not allow the visitor to get the feel and sound of a musical instrument, they certainly help to understand the multisensorial possibilities that these objects offer. On this note, Martin Perkins (Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, Birmingham) embarked on the exploration of digitalizing the multisensorial features of a musical instrument to present them in their context and musical function without endangering their preservation. Indeed, digitalization and interactive media with musical instruments can serve as an amplifying lens that can explore the cultural significance of musical instruments that go beyond the object.

The socialness of a musical instrument relies on its capacity to connect and to be linked with other cultural entities. As Rossi Rognoni stated: ‘social objects allow people to focus their attention on a third thing rather on each other, making interpersonal engagement more comfortable.’ It is this potential that, as Tim Corum (Horniman Museum) showed us, allows inclusiveness with the museum collection through the participation of visitors in a community of practice. Joe Sullivan (Natural History Museum) touched the same concern with his talk on the effective strategy of the Royal Air Force Museum in basing Museum musical activities based on the objects in the collection and their relationship to the community. Perhaps any museum could act as a social center for people to have interpersonal relationships using musical instruments as third objects. In some way, whenever possible a playable instrument is a plane good strategy for emotionally engaging with the visitors. Such is the case of Gustav Holst’s piano, which functions as the composer’s relic, making visitors feel like the composer of The Planets is there playing in the room.

Alice Little explained how the Anthony Baines Archive at the Bate Collection of Musical Instruments offers new insights into understanding the cultural context in which a curator forms a collection. According to Little, the recently begun research project now focuses on Bate’s collecting rationale: ´how he chose items, where he found them, why he chose to give them away or sell them´. Moving further afield, Holly Trubshawe, showed us how the cultural significance of a musical instrument expands beyond the object itself towards the associated materials. For Trubshawe, ‘with a missing object or missing part of the story, it is about choosing whether to focus on the gap or to focus instead on the information and materials you do have. ‘

Touching on the social potential of musical instruments and resonating with Professor Rossi Rognoni’s talk, Simon Waters presented his perspective on how woodwind design and manufacture in London can be understood as a cultural phenomenon produced by the entanglement of different human and non-human cultural entities. Waters’ opinion, rooted in Actor-Network Theory (ANT), centres on the gathering of multiple forms of expertise involved in a case study and in the equal consideration of human and non-human actors (instruments, workshops, institutions, addresses and so on) as crucial participants in the creation and re-creation of a musical instrument and its cultural significance. When you study musical instruments, you find yourself studying other subjects you would never thought you would. You find yourself asking advice of people of all sorts of backgrounds such as amateur, enthusiasts, collectors, curators, conservators, performers and builders. Taking on the challenge of learning musical instruments, you find yourself studying about a wide range of subjects such as physics, mathematics, art history and chemistry, architecture and philosophy. Such is the social power of musical instruments, and we should be able to let the public be transported from one link to another inside these networks. The challenge comes in interpreting the meaningful connections that an instrument can have. As Simon Waters mentioned, by ‘following the actors’ involved in the creation of the meaning of a musical instrument, the networks can appear. However, a musical instrument interacts with so many entities, it can be difficult to distinguish the significant ones that trace social connections in fresh and interesting ways. The curator’s challenge also lies in identifying and presenting what Bruno Latour, the founder of Actor-Network Theory, calls intermediaries and mediators. The first would be an entity that transports a meaning without any transformation, while the latter ‘transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry (Latour, 2012:39).’ Identifying the mediators for musical instruments facilitate the spotting of the meaningful links worth discovering.

Exceptionally made musical instruments such as ´The Extraordinary Royal Flute´, presented by Ashley Solomon (Royal College of Music), are often compared to works of art. The visual qualities and symbolic associations with power and social status explain why these instruments are usually wanted by museums and private collectors alike. However, according to Arnold Myers, these beautiful examples are often allowed to overshadow the common musical instruments that, despite having an enormous social value, are relatively ignored by museum collections. Myers brought to our attention a case point: the story of the Salvation Army as a provider of brass instruments for large parts of British society from 1889 to 1972.

The concertinas and mouth organs carried by soldiers during the Great War are also perfect examples, according to William Quale, of how a common instrument that was mainly produced for amusement was transformed into a carrier of humanity and national identity in the most critical moments when people’s lives were on the line. I wished that Ashley Solomon had gone into more in-depth about what constitutes a work of art for him and under what circumstances we can say that musical instruments are art. The social consensus often involved in labeling an object as art is, in fact, as interesting as the artwork itself.

On a similar note, Kathleen Wiens reminded us how the interpretation of musical objects can inspire emotions and reinforce a social conscience through her visual and sonic exhibition at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights about the political struggle of the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa. More on the social side of musical instruments, Verena Barth showed how the trumpet is used to construct social codes and affirm gender identity. The trumpet, according to Barth, has been associated with virtuosity or ´exceptional artistic or intellectual achievement´, which, in jazz and elsewhere, leads to the use of the body language to emphasize masculinity. The gender study of musical instrument is always interesting. The guitar was often associated with masculine values, however, over the years has passed to be also used by strong female performers from the folk scene such as Joan Baez, Joni Mitchel, and PJ Harvey. The guitar being the core instrument for the Mexican song, was for a time exclusively associated with men and their love for women. Later, however, it was placed in the hands of strong female characters including Latin-American artists such as Violeta Parra, Chavela Vargas and Lila Downs. Perhaps we have not yet deciphered the exact moments where musical instruments become symbol carriers and what entities come in to play to make those associations happen.

The Joint Conference of the Social History Curators Group (SHCG) and the Musical Instruments Resource Network (MIRN) was an amazing opportunity to broaden our perspective and deepen understanding of how to tell social histories through musical instruments. This initiative goes hand in hand with the relatively general concern of redefining the aims and methods of organology. As Gabriele Rossi Rognoni indicated at the beginning of the conference, there is an incredible amount of work to be done mainly residing in building a general theory and ethos of how and why musical instruments interact with human beings, social spaces, repertoire, and economics. We still need to find a way of exciting people throughout the interaction with historical musical instruments in the same way we musical instruments lovers feel when we play, make, listen and study them.

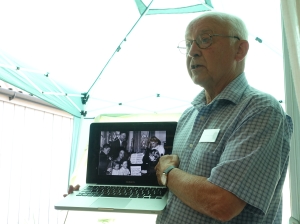

The Square Piano Workshop Study Day, sponsored jointly by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Horniman Museum and Gardens took place on 27 July 2018. David Glynn reports:

In 2016 the renowned Finchcocks Museum of early keyboard instruments closed, and the majority of the collection was sold. Three of the instruments were purchased by the Horniman Museum, with the assistance of the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF); one of these was a square piano made by Adam Beyer of London in 1777. With HLF funding, the Horniman Museum commissioned Lucy Coad, the well-known square piano specialist, to restore this instrument to playing condition.

On 27 July 2018, the Horniman Museum arranged a Study Day focusing on the Beyer piano, held in Lucy Coad’s workshop in the hills near Bath. As an enthusiast for the delights of the square piano, I was delighted to attend this event, which promised to be informative on Beyer and his instruments, and on the Horniman’s plans for the piano. It was also a great privilege to have the opportunity to visit Lucy’s workshop.

The day started with a talk about Beyer himself by Michael Cole, an authority on the early piano. We learned that his name should be pronounced “buyer”, and he was responsible for some of the finest cabinet-work of the period. Beyer was one of an important group of piano makers in late eighteenth-century London, many of whom were German born. Indeed, on the basis of a note by the much later John Shudi Broadwood, it has been supposed that Beyer was originally German.

Michael Cole doubts this theory and outlined his researches into Beyer’s origins, based on genealogical and other contemporary records. We were introduced to a portrait of Katherine Beyer who was Adam’s sister and was pivotal in the investigation. Unfortunately, the outcome of this research was inconclusive, but we gained many fascinating insights, such as Beyer having bought a house in Hampstead in 1782; this would have been impossible if he had been a foreigner, and there appears to be no record of him ever having been granted British citizenship, from which one might conclude that he was British by birth. I was amazed to discover that one of Beyer’s descendants is Elizabeth Wallfisch, the baroque violinist, whom I have seen many times leading the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. This seemed to bring the eighteenth century closer.

We then gathered around the instrument itself for a discussion by Lucy about its construction, its history and her plans for restoration. The piano was previously restored around 1980 at Finchcocks by Alastair Laurence. In a letter, Alastair recalled the piano’s history at Finchcocks. Over a period of 34 years it must have been used around 2000 times in demonstrations on Open Days – always with the same piece by Cimarosa, to demonstrate the lid swell. Of which piece, Alastair became somewhat tired! He must have tuned the Beyer over 500 times, and recounted that it was always a reliable instrument at Finchcocks.

Lucy had removed the soundboard from the instrument so that it and the bridge, both of which had become seriously twisted, could be flattened.

This enabled us to see the main structural members beneath the soundboard, which was most educational in terms of understanding the construction of square pianos. It also enabled us to appreciate the astonishing quality of Beyer’s workmanship, which Michael Cole regards as being comparable to Chippendale. Another aspect of this craftsmanship was the neatness and beauty of the guide lines incised on the soundboard to mark the positions of the tuning pins, and the neat annotations of the notes next to each pin. Lucy had another similar Beyer instrument in the workshop, and a third Beyer piano was also present courtesy of David Hunt. Comparison of these instruments was fascinating, both in terms of similarity of construction, and differences in condition.

There was discussion as to the relative merits of preservation and conservation, particularly in regard to the outer hammer coverings. Should these be conserved or replaced (as contemporaries would have done)? Such choices will affect the tone of the instrument. Lucy plans to preserve the original hammer coverings. Mimi Waitzman observed that the original sound of an instrument is always conjectural – authenticity of sound is a chimaera. Despite that, the aim is to get as near to “authenticity” as knowledge allows. This brings the listener something of the materiality of that time. People do respond to that.

Mimi commented on the self-consciously ‘English’ look of the Beyer piano, typical of the Georgian furniture of its time. The beauty of the instrument lies in the attractive unadorned wooden veneers, its harmonious lines and proportions. This taste had its genesis from shortly after the Civil War, when the English began to regard painted and highly ornamented surfaces on furniture as vaguely seditious, smacking of ‘Continental Popery’.

After an excellent lunch in which we could talk to our fellow participants and take in the beauty of our surroundings, Mimi Waitzman outlined the Horniman’s plans for the Beyer square piano.

It will join the Kirkman harpsichord of 1772 in the ‘At Home with Music’ display in the Music Gallery. Conservation work having returned both the Kirkman and the Beyer to optimum playing condition, the instruments, together with a late 18th-century English Chamber Organ and an Italian virginals by Onofrio Guarracino (1668), will be used in a series of weekly public performances. It is anticipated that the Beyer will be featured on average, once per month. It will be wonderful to hear the instrument speak again.

Many thanks are due to the Horniman Museum, The Heritage Lottery Fund and to Lucy Coad and her team for such an absorbing day.

ORGAN WORKSHOP STUDY DAY REPORT

The Organ Workshop Study Day, sponsored jointly by the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Horniman Museum and Gardens took place on 27 April 2018. Adriel Yap reports: (The original version of this article was published in the Institute of British Organ Building’s Newsletter No.90, June 2018.)

The Horniman Museum and Gardens organised a study day focusing on an anonymous organ from the late 18th early 19th century which it purchased from the sale of Richard and Katrina Burnett’s collection of keyboard instruments from Finchcocks in 2016. The instrument is being restored so it can join next year the ‘At Home with Music’ display, which tells the story of domestic keyboard instruments.

The restoration of the organ is part of a larger 4-year project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF). While the Horniman’s present collection of displayed keyboards already includes one playable instrument – a late 18th-century English harpsichord – the restored organ and two other Finchcocks instruments will augment the number. An enhanced programme of weekly performances, a competition and master classes will accompany the additions to the display. The study day on 27 April was part of the project and funded by the HLF. About twenty people, including other keyboard specialists, attended.

The first part of the day was spent looking at the technical aspects of the restoration presented by Dominic Gwynn. The organ is typical of domestic instruments of the period but had few identifying marks. It may have been made by an experienced organ builder with other crafts called in to make the case and decorative front pipes (in wood).

As is often the case, restoring an instrument presents issues to the organ builder to resolve. A key issue is how far should the organ be modified from its present condition. For example, it was decided to use screws to replaced nails so that parts could be easily dismantled for repair in the future. It was also decided to refinish the case and replace the modern worn cloth with a silk backing that would have been similar in colour and texture to the original, behind the sham front pipes.

This would also help anchor the context in which the instrument was seen and used, that is in the home of the increasingly wealthy and culturally aware commercial classes of the day.

After a very enjoyable lunch, Mimi Waitzman, Deputy Keeper of Musical Instruments, spoke about the restoration from the perspective of the Horniman Museum.

The music gallery attracts more than 400,000 visitors each year, and many visits are organised by schools. The Museum sees its role as one of preserving important artefacts and to make them as accessible as possible through gallery curation, and documentation. But it also sees a role for itself in developing new art works and increasing public engagement with its collections. With increasing competition for funding, there is a need for closer collaboration between key players in the musical instrument museum sector.

Making an instrument available to play presents challenges to any museum. Playing an instrument without proper supervision and conservation support may lead to an accelerated deterioration through wear and tear, damaging rare or even unique primary evidence contained in the object. Yet it is also important that the main function of the instrument be conveyed and better understood. But all of this must be balanced against the knowledge that instruments such as this organ, are a finite and irreplaceable resource. So there is a clear responsibility for the Museum to ensure that a prudent balance is maintained between access, including use, and conservation.

What I enjoyed most about the study day was the range of disciplines represented in its participants. Being able to learn from non-organ builders is always useful and the discussions we had over lunch will certainly inform decisions I make when faced with similar issues. It certainly has given me a wider perspective of how we should undertake historically informed restorations of organs that come my way.

- An excellent Report on the MIRN conference, held on 12 October 2017, has been published in the current Galpin Society Newsletter, p.5.

- Several MIRN members attended the one-day workshop on ‘Music & Material Culture‘, held at the University of Cambridge on Wednesday, 7 December. Mimi Waitzman (Chair, MIRN) writes:

The one-day conference in Cambridge, billed as a ‘workshop’, on Music and Material Culture brought together an array of disparate topics that attempted to give shape, substance and meaning to the very broad theme. We learned of many ways that material manifestations of music and music-making extend beyond musical scores and instruments to furniture, buildings, scientific endeavour and even philosophies of exhibiting music and musical materials in museums. The different relationships that societies construct between music and the other arts were also explored. All-in-all, a stimulating day with many mind-opening discussions and presentations.

- MIRN members Jenny Nex (Secretary) and Arnold Myers attended the Museums Association Conference in Glasgow on 7-9 November where they represented MIRN at a stand dedicated to all Subject Specialist Networks (SSNs). Jenny writes:

Representatives of MIRN contributed to the presence of Subject Specialist Networks at the Museums Association Conference in Glasgow in November. The trade fair area, which included representatives from a wide range of businesses and organisations which support museums, their staff and their users, was a busy space, particularly at break times. Conference delegates were able to meet representatives from a number of the different networks and to find out more about us and what we offer. It was important for MIRN to be visible here since many collections contain at least one musical instrument and most collections don’t have a musical instrument specialist. It was also useful to meet representatives from other networks and to discuss ways which we could work across networks in the future.